Nov 20, 03:35 pm

Wildfires and Dead Palm Trees Haunt the L.A. Dream in Zoe Crosher’s New Show | Seen | New York Mag | Nov 17, 2018

Wildfires and Dead Palm Trees Haunt the L.A. Dream in Zoe Crosher’s New Show By Michael Slenske

Zoe Crosher, Sunlight As Spotlight at Patrick Painter Gallery.

The allure of Los Angeles has long-balanced on the razor’s edge between fantasy and reality, but lately, with the wildfires and the mudslides and the dying off of the city’s trademark palm trees — most of which weren’t native anyway — and, now, even more deadly conflagrations that have turned fall rainy season into fire season, it’s become a bit too real.

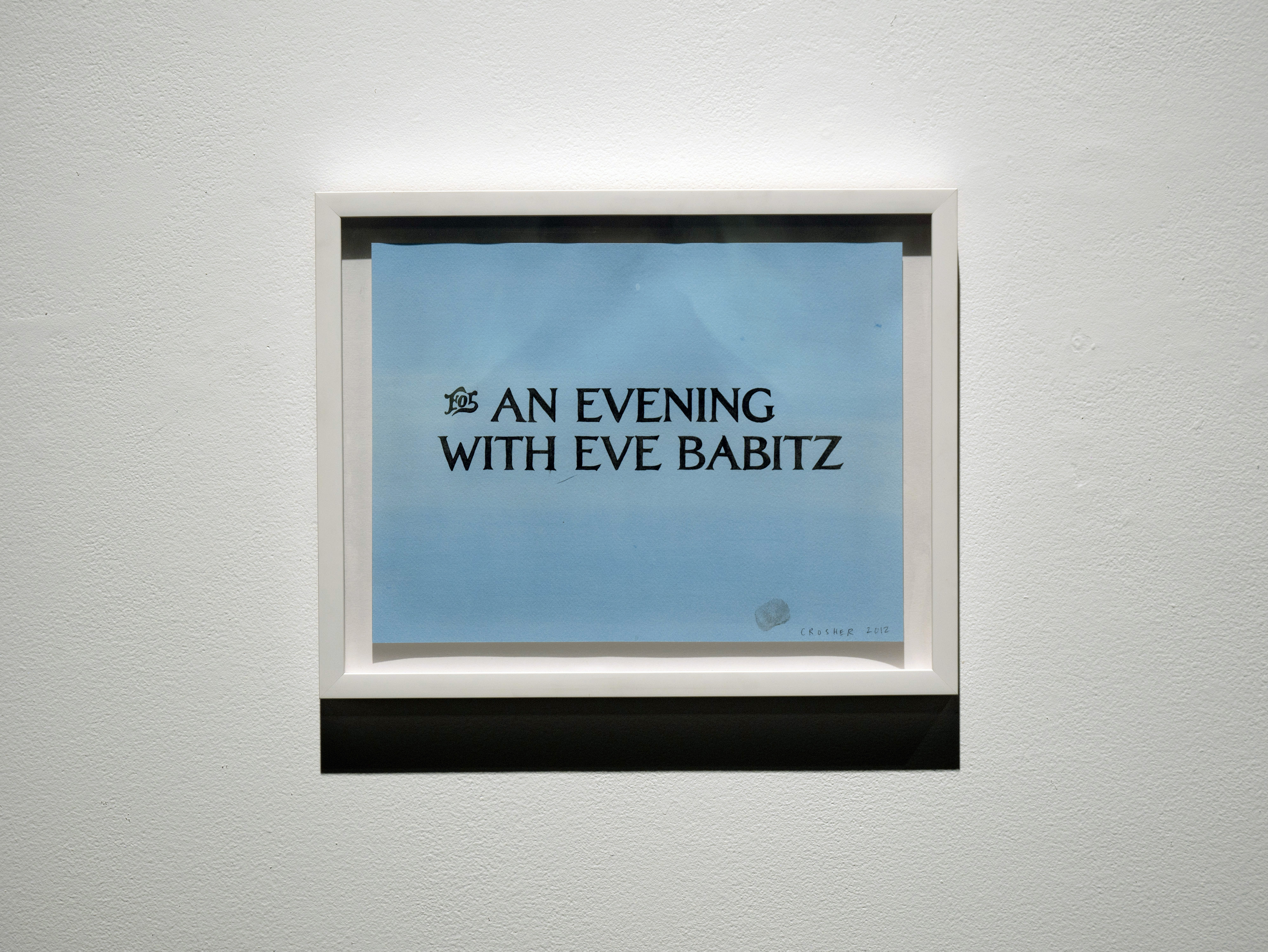

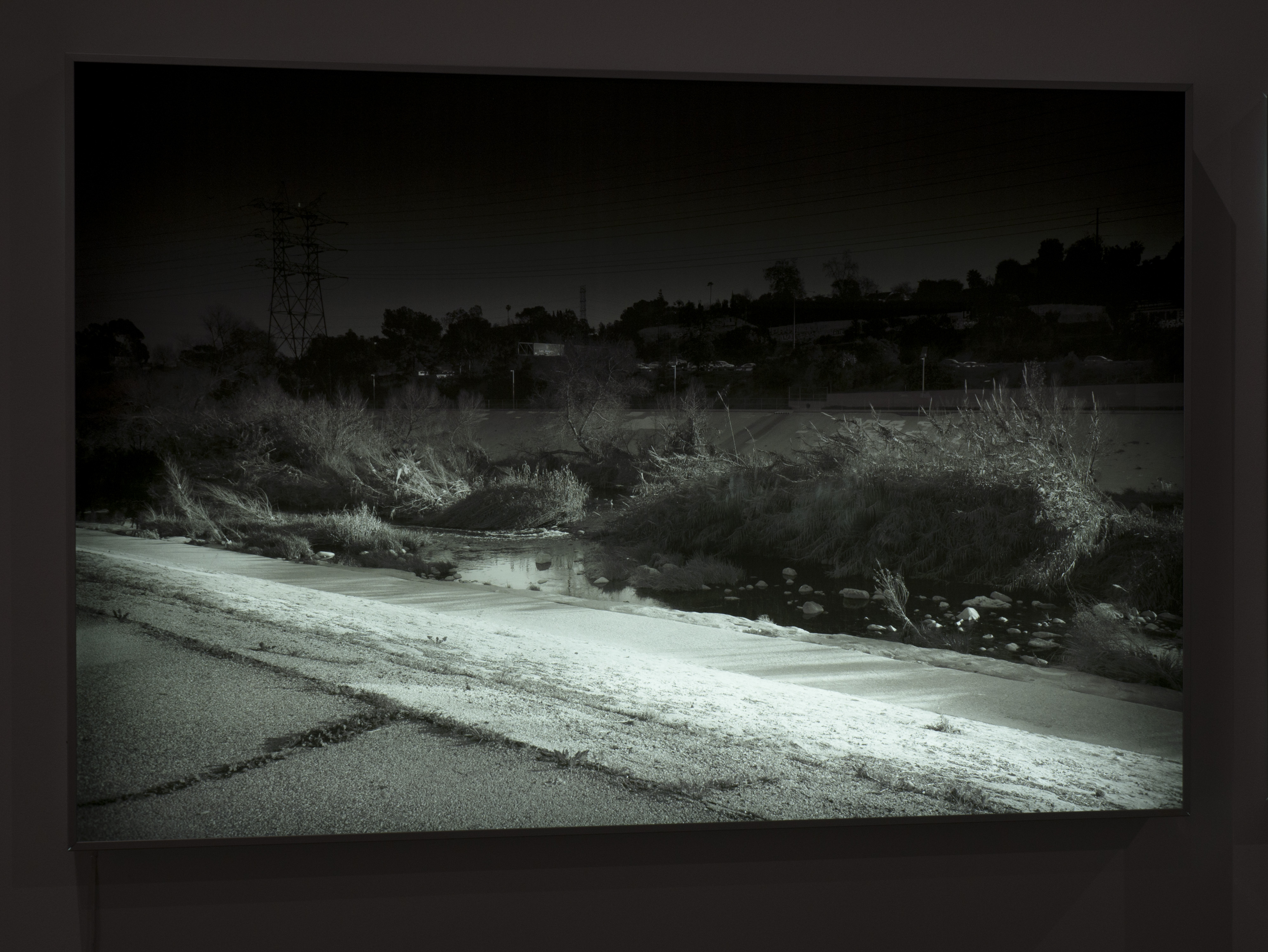

Zoe Crosher, who was born in Santa Rosa, California (but grew up abroad the daughter of diplomat), moved to L.A. to get her MFA at CalArts in the early aughts. She’s been mining the vein of this liminal space between the image of L.A. and the actual place in photographic (and sculptural) bodies of work inspired by everything from the fiction of Eve Babitz, the reclusive L.A. writer who has lately had a bit of a comeback, to the decline of the palm tree and the Los Angeles River. Crosher, who was a standout of the New Photography 2012 survey at MoMA for the Michelle duBois Project , again draws on this trio of utterly Angeleno influences for Sunlight As Spotlight, her solo debut at the Bergamot Station gallery of Patrick Painter, which features four 48-by-72-inch light boxes of images shot using the silent-film-era technique known as “day for night” to capture what climate change and environmental management has left of the L.A. River.

But last weekend, Crosher’s artist talk, which was supposed to begin with a reading from Babitz’s Slow Days, Fast Company, was nearly canceled (only a few folks made it out) amid the chaos of the Woolsey Fire. In a sense, the world had quite literally caught up to Crosher’s investigations.

Day for night “was done during the old days of film when they didn’t have money to shoot at night, so they used all these crazy filtration systems to make it look like day, so you have all these beautiful hiccups in film noir where you’ll see clouds in the sky at night and things that just don’t make sense,” says Crosher. She merged these analogue techniques with digital photography to create work that not only comments on the death of the river — including the attendant palm trees, one of which is captured sans crown like a beheaded sentry — but on the slow creep of global warming, water politics, star culture, and westward expansion. Her images use surface and tricks of light, exposing the cracks in the veneer of this idyllic L.A., to probe deeper into the dark realities that lie just beneath that surface.

On the floors of the gallery are bronzed palm fronds, which were found on the sides of L.A. streets and freeways then transformed into sculptures using lost wax casting. (This L.A. icon — varieties that were mostly imported from elsewhere — are being killed off by fungus and invasive insects. Instead of replacing them with new palms, the city has chosen trees that tolerate drought better and provide more shade.) Crosher’s casts serve as a “pre-archiving of the death of Los Angeles” that document the demise of this outmoded emblem of the L.A. fantasy.

“The actual palm frond is covered in wax then covered in concrete, and then it gets burned out and filled with bronze, and in a photographic sense that is really exciting because the bronze becomes the palm frond,” explains Crosher. “It’s beyond anything photographic, it’s basically what photography only ever wishes it could be in terms of archiving. No matter how close I photograph L.A., I can never get it this close.”

The metaphor of a dried-out palm frond being consumed by molten bronze is not — or perhaps should not — be lost in this moment when President Trump is falsely accusing the Bureau of Land Management, not climate change (much less art-washing water hoarders) for causing these fires. All the creative-class chieftains flooding social media with neoromantic devastation-porn images of the fires in Malibu and Ventura County, might do themselves a favor by having a quiet meditation among Crosher’s erie, if razor-sharp, “pre-archival”

This is the Babitz excerpt she’d planned to read:

Ever since the Garden of Allah was torn down and supplanted by a respectable savings and loan institution, the furies and ghosts have made their way across Sunset to the Chateau Marmont. The Garden of Allah was originally the villa of Alla Nazimova, a great silent star, until one night when a fire swept down Laurel Canyon, and she was forced to decide what she wanted to save from her grand house — what, in fact, she wanted at all. And she suddenly knew that the flames could consume all she owned, she would leave for New York at once; there was no point in owning anything in Hollywood, and in this she had a curious premonition or grasp of “place.” It’s a morality tale of the unimportance of material things, though there are those who will say it’s about how awful L.A. is.

“I didn’t need to read it, it was already happening,” says Crosher, who notes that her work has been “plotting this [reality] for so long, it’s been this slow accumulation of all these various elements that have to do with my troubled love affair with Los Angeles.”

And in the end, “I’m really proud of the show, but it was really like the end is nigh, and it was a little too close; there was not enough distance. That’s why I’m back in New York. Bring on the snow,” says Crosher, who recently moved to Brooklyn after two decades in Los Angeles, and left the city two days early amid the flames. “I can handle the fantasy; I can handle the end of the fantasy — when I’m far away from it.”

Meanwhile, on Friday morning, a brush fire broke out in the Hollywood Hills, though it was quickly put out before threatening any homes. This time.

News & Events

- ARTFORUM REVIEW “The Swimmer” The FLAG Art Foundation by David Coleman, Oct 2024 Print Posted November 23, 2024

- Library Street Collective and the Shepherd, Detroit present GRACE UNDER FIRE - Oct 24, 2024 through Jan 11, 2025 Posted November 23, 2024

- "A Masterpiece of Fiction Inspires the Urge to Submerge in a Gallery Crawl In New York’s art show of the summer, paint and prose meet in “The Swimmer,” a psychoanalysis of John Cheever’s suburban nightmare of 1964." NY Times Critic's Pick by Walker Mimms Posted July 4, 2024

- The FLAG Art Foundation invites you to join us for the opening reception of The Swimmer, an expansive group exhibition inspired by John Cheever’s 1964 short story of the same name at The FLAG Art Foundation, on Thursday, June 6th, from 6-8pm. Posted June 5, 2024

- HOLLYWOOD DREAM BUBBLE: Ed Ruscha's Influence in Los Angeles and Beyond Opening Tonight in Los Angeles! Posted April 27, 2024

- THE ELEMENTAL invites you to join us Saturday March 2, 2024 from 6:30-10pm for the opening reception for the new iteration of our evolving exhibition: THE GAIA HYPOTHESIS Chapter Two 2.0: Palm Trees Also Die Posted February 29, 2024

- THE GAIA HYPOTHESIS CHAPTER TWO: PALM TREES ALSO DIE Friday, November 17th, 2023 Opening Reception 6pm - 10pm THE ELEMENTAL Palm Springs, California Posted November 16, 2023

- Recent Acquisitions Zoe Crosher California Museum of Photography November 18, 2023 to March 30, 2024 Posted November 16, 2023

- The way Eve Babitz wrote about art in Los Angeles was art in itself, LA Times, December 21, 2021 by Christina Catherine Martinez Posted December 21, 2021

- Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University acquires Prospecting Palm Frond Posted July 1, 2021

- Silver Art Projects Inaugural Evening Expo Thursday, May 6, 2021 | World Trade Center | New York City, NY Posted May 3, 2021

- In Auction: moCa Cleveland: Benefit Auction 2021 Posted May 3, 2021

- Prospecting Palm Fronds on cover of publication of To Bough and To Bend, Los Angeles, CA Posted December 9, 2020

- Announcing Participation in the Inaugural Silver Art 2020 Cohort, WTC / NYC Posted July 28, 2020

- Peralta Projects 'Motel' exhibition, discussion examines 'home' in an unprecedented era Opens on July 13, 2020 Posted July 10, 2020

- After Quarantine / A Fundraiser for EFA Posted June 16, 2020

- Venice Family Clinic 50th Online Benefit Auction! May 3-19, 2020 on Artsy Posted May 5, 2020

- #PleaseSupportTheCause #ArtsyBenefitAuction Spring To Action! Posted April 16, 2020

- To Bough and To Bend, opening today at Bridge Projects in Los Angeles from 12-7pm, through April 25, 2020 Posted March 14, 2020

- VIP Studio Visits at The Elizabeth Foundation of the Arts, Saturday, March 7, 2020 / 2–4 PM Posted March 6, 2020

- Mae Wested from the Disappearing of Michelle duBois in the Monica King Contemporary Art Grotto, New York, NY Posted February 1, 2020

- L.A. on Fire Catalogue available now Posted January 15, 2020

- Reading for Slouching Towards Los Angeles this Saturday, December 14th at Wilding Cran Gallery from 2-4pm Posted December 13, 2019

- Five more Out the Window (LAX) images acquired by LACMA Posted December 7, 2019

- Going Beyond the Photo-Archive The Significance of Fantasy and Photo-Reflexivity in Zoe Crosher’s The Michelle duBois Project, by Yonit Aronowicz Posted November 30, 2019

- Opening Saturday night! L.A. on Fire, curated by Michael Slenske at Wilding Cran Gallery Posted November 14, 2019

- Starting Something New: Recent Contemporary Art Acquisitions and Gifts at Mead Art Museum, Amherst, MA, on view now through July 26, 2020 Posted October 18, 2019

- Inclusion in Conversations with Artists II, By Heidi Zuckerman Posted October 17, 2019

- On the occasion of @nyrbooks release of a new collection of essays by #EveBabitz this week... Posted October 11, 2019

- Zoe Crosher in The Watermill Auction, The Hamptons, July 27, 2019 Posted July 12, 2019

- Prospecting Palm Fronds published in new issue of Full Blede / Issue Seven: The Continuant January 2019 Posted January 18, 2019

- Please Support the 24th Annual Artwalk NY Coalition for the Homeless, Nov 27, 2018 Posted November 27, 2018

- Wildfires and Dead Palm Trees Haunt the L.A. Dream in Zoe Crosher’s New Show | Seen | New York Mag | Nov 17, 2018 Posted November 20, 2018

- An Artist Talk with Zoe Crosher this Saturday, November 10th at 2 p.m. at Patrick Painter, Inc. Posted November 7, 2018

- Zoe Crosher's "Sunlight as Spotlight" opens at Patrick Painter on October 19th Posted October 10, 2018

- Check out Zoe Crosher's Art Work | VoyageLA | August 13, 2018 Posted August 13, 2018

- LA Times Review: As planes take flight at LAX, two photographers find a darker reality below in 'Grounded' at ESMoA, Aug 3, 2018 Posted August 3, 2018

- Paradise Lost: Zoe Crosher, Bernt & Hilla Becher, Joshua Hagler at Patrick Painter Gallery Posted July 27, 2018

- The Philip Johnson Glass House 2018 Auction, June 9 LA-LIKE: Escaped Exotics (set of 5) Posted June 8, 2018

- GROUNDED, John Divola and Zoe Crosher Approach LAX from Different Directions, opening at ESMoA on June 2nd, 2018 Posted May 24, 2018

- An Artist Memorializes The Disappearing Palm Trees of Los Angeles - JStor Daily April 24, 2018 Posted April 24, 2018

- Inaugural Los Angeles My Kid Could Do That Benefit, April 6-8, 2018 Posted April 4, 2018

- Art Matters: Heidi Zuckerman in Conversation with Zoe Crosher Posted March 13, 2018

- CURIO exhibition and Fainting Club, curated and presented by Yasmine M. Zodeh and Sandi Turner Posted March 8, 2018

- Wanderlust: Actions, Traces, Journeys 1967-2017 opens at The Des Moines Art Center Posted February 19, 2018

- Zoe Crosher to judge 2018 Golden Pear Award, designed to raise interest & awareness for independent & artisan perfumers ~ London, April 2018 Posted February 1, 2018

- Publication of Wanderlust: ACTIONS, TRACES, JOURNEYS 1967-2017 Catalogue ~ Essay by Melanie Flood Posted February 1, 2018

- Zoe Crosher, The Imagiatic ~ UCLA Lecture & Studio Visits, January 26, 2018 Posted December 23, 2017

- Zoe Crosher at the Aspen Art Museum, Opening December 15th, 2017 ~ Prospecting Palm Fronds Posted December 11, 2017

- Virago at Hilde Gallery, Los Angeles / Opening reception: Saturday, November 11 / 6 – 9pm Posted December 10, 2017

- WANDERLUST: ACTIONS, TRACES, JOURNEYS 1967-2017 Opens September 7th at UB Art Galleries Posted September 14, 2017

- Two Truths & A Lie, August 24th - September 30th, 2017. Artist Talk: Zoe Crosher Thursday, August 24 | 5:30 p.m. Posted August 18, 2017

- ArtCrush Auction 2017, August 2–4, 2017 Aspen, CO Posted July 30, 2017

- Zoe Crosher listed as Cultural Influencer and Innovator in Summer 2017 Issue LAC Magazine Posted June 21, 2017

- Zoe Crosher is Artist-in-Residence at Marble House Project in Dorset, VT Posted June 20, 2017

- Art Seed Artist Talk at the Marble House Project Posted June 20, 2017

- Deconstruction, the 11th Los Angeles Fainting Club Posted June 14, 2017

- Steve Turner L.A. is pleased to present All the Small Things, an exhibition of Los Angeles-based artists featuring works that do not exceed six inches in any dimension. Posted June 1, 2017

- Zoe Crosher in Residence for 2017 at the Wende Museum, a collections-based research and education institute that preserves Cold War artifacts and history. Posted May 11, 2017

- Zoe Crosher in LACE BENEFIT ART AUCTION | Wednesday May 10, 2017 7-9 PM Posted May 2, 2017

- Zoe Crosher & Catherine Wagley at DFLAT Residency, Mexico City, March 18-28, 2016 Posted March 26, 2017

- The Fainting Club in Palm Springs inspired by the current exhibition at The Palm Springs Art Museum: Women in Abstract Expressionism Posted March 1, 2017

- Joanie 4 Jackie, Zoe Crosher brings Miranda July and Astria Suparak to CalArts during their Pacific Coast Tour, November 13, 2000. Posted February 17, 2017

- SUPERNATURE, Organized by Zoe Crosher & Emma Gray at Five Car Garage Los Angeles, CA, January 2018 Posted February 16, 2017

- Panel Discussion / Art in the Age of Donald Trump at Art Los Angeles Contemporary Posted January 24, 2017

- Amplify Compassion: An Art Sale to Benefit the ACLU at 356 S.Mission / Los Angeles, CA Posted January 19, 2017

- Floral Patterns ~ An Essay About Flowers And Art (with a blooming addendum.) by Andrew Berardini for Mousse Magazine Posted October 9, 2016

- The Very 1st Cambridge, Massachusetts Fainting Club Dinner, hosted by Alison Nordström & Lucy Soutter Posted October 2, 2016

- Zoe Crosher in Human Condition, curated by John Wolf, at the recently abandoned Los Angeles Metropolitan Medical Center Posted September 30, 2016

- Zoe Crosher at SFAI The Visiting Artists and Scholars Lecture Series Tuesday, Sept. 20, 2016, 7:00PM - 9:00PM Posted September 14, 2016

- In conversation with artist Zoe Crosher, Howard Rodman, and Hunter Drohojowska-Philp, Matthew Specktor discusses and signs Eve Babitz’s Slow Days Fast Company: The World, the Flesh, and L.A. Posted August 29, 2016

- Madames Electric at The Pit for Carla l.a. | Snap Reviews by Aaron Horst, July 16, 2016 Posted July 21, 2016

- Invitation for The Very First Paris Fainting Club, Weds 29 June - 8pm ! Posted June 29, 2016

- Zoe Crosher "The New LA-LIKE" at Mayeur Projects, Las Vegas, New Mexico, Opening Night June 23rd Posted June 9, 2016

- "Madame Electrics," curated by Shana Lutker, at The Pit, Los Angeles, June 12th Posted June 5, 2016

- LA-LIKE: Transgressing the Pacific, by Kate Sutton for Bookforum Posted June 1, 2016

- Zoe Crosher reading // The Institute for Art and Olfaction launch scent zine of 'Now Past Later,' May 26th, Los Angeles Posted May 21, 2016

- The Fainting Club Summer Supper in London, May 24th, hosted by Lucy Soutter & Susan Hyland Posted May 21, 2016

- Hesse Press at Offprint London 2016 at the Tate Modern - Book Signing this Saturday 1-2pm Posted May 16, 2016

- Hammer Museum present AIX Scent Fair, May 6-8, Los Angeles, "The Elevator Series Scent - HW 8:13pm" Posted May 2, 2016

- Imperceptibly and Slowly Opening at Vox Populi, May 6th in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Posted May 2, 2016

- Catalogue Launch For Staging Los Angeles: Reality, Fantasy, and the Space Between, USC, Los Angeles, April 26th Posted April 16, 2016

- Mae Wested no. 1 to become part of Pérez Art Museum Collection, Miami, Florida Posted April 14, 2016

- Memory Theater, Directed by Srijon Chowdhury, Presented by Upfor, opening April 13th, Portland, Oregon Posted April 10, 2016

- MTV RE:DEFINE 2016, Presented by The Joule, Dallas, Texas, April 8th with the Michael Goss Foundation Posted April 4, 2016

- Shades of Gray by Andrew Berardini, reading at Human Resources, Los Angeles, April 1st Posted March 29, 2016

- NeueHouse Presents: The Fainting Club 'The Dust Dinner' with Zoe Crosher, March 23rd, Los Angeles Posted March 20, 2016

- LA IN THE AUGHTS: Art Auction and Party to Benefit X-TRA and Project X in Los Angeles, March 13th Posted March 12, 2016

- Zoe Crosher Joins the Advisory Council for the Arts at Cedars-Sinai Posted March 1, 2016

- Mayeur Projects Inaugural Artist-In-Residency Zoe Crosher, Las Vegas, NM, March 17 - May 14th Posted February 16, 2016

- LeSwim announces LeSwim x Zoe Crosher at Rob Pruitt's Flea Market, Presented by LAND Posted February 11, 2016

- Book Release for LA-LIKE: Transgressing The Pacific at LA Art Book Fair, MOCA Geffen Contemporary, Los Angeles, February 12th Posted February 8, 2016

- Artist: Zoe Crosher, by Caroline Ryder for Distinct Daily Posted February 3, 2016

- LA-LIKE: Transgressing The Pacific, published by Hesse Press, 2016 now available Posted February 1, 2016

- Art House at Soho House Hollywood, curated by Sharón Zoldan, February 1st Posted January 28, 2016

- photo l.a. panel discussion, January 22nd, 2016 at The REEF/LA Mart, Los Angeles Posted January 18, 2016

- Announcing the publication of LA-LIKE: Transgressing The Pacific, published by Hesse Press, 2016 Posted January 8, 2016

- Mayeur Projects Announces Inaugural Artist in Residence - Zoe Crosher, March 2016, Las Vegas, New Mexico Posted December 14, 2015

- The Fainting Club Holiday Party in Los Angeles, December 11th Posted December 11, 2015

- Los Angeles County Museum Of Art to acquire work from Out The Window (LAX) Series Posted November 29, 2015

Projects

- LA-LIKE: Sunlight As Spotlight

- LA-LIKE: Prospecting Palm Fronds

- LA-LIKE: Escaped Exotics

- LA-LIKE: Transgressing the Pacific

- LA-LIKE: LA Imaginary As Unlit Lightboxes

- LA-LIKE: Fools Gold Dust (Mimic) Paintings

- LA-LIKE: Day For Night (or Sunlight As Spotlight)

- The Manifest Destiny Billboard Project, in conjunction with LAND

- LA-LIKE: Mirage

- Shangri-LA'd & Expanded Shangri-LA'd

- LA-LIKE: Composition I-10, Desert Center

- The Manifest Destiny Billboard Perfume

- LA Disappearing Frond-Like

- LA-LIKE: Transgressing the Pacific, Dessert Concepts & Recipes

- For An Evening with Eve Babitz, at the Chateau Marmont

- Tear Sheet Posters

- LA-LIKE (LOST)

- LA-LIKE: LAXART Billboard

- The Pools I Shot

- LA-LIKE

- The Uniqued Series

- The Additive Dust Series

- Mae Wested

- The Disbanding of Michelle duBois

- The Vanishing of Michelle duBois

- The Disappearing of Michelle duBois

- The Other Disappeared Nurse

- Silhouetted

- All Her Shadows

- Blackened Last Four Days & Nights in Tokyo

- Almost the Same

- The Unveiling of Michelle duBois

- The Unraveling of Michelle duBois

- Posed Postcards

- Polaroided

- The Reconsidered Archive of Michelle duBois

- Obfuscated

- LA-LIKE: Escaped Exotics / The Bronzed Blossoms of Madame, published by X Artists' Books

- The Good & The Glamorous, A Memoir of Misremembering & The Cold War

- LA-LIKE: Transgressing the Pacific, Published by Hesse Presse, Los Angeles, CA - Spring 2016 (Sold Out)

- Both Sides of Sunset: Photographing Los Angeles (May 2015) Published by Metropolis Books

- Forthcoming: The Re-duBois Book

- Returning to Berlin / Publication curated by Kim Schoen - Motto, Berlin (August 2013)

- Why Art Photography? by Lucy Soutter (2013) Published by Routelage

- Volume 4: The Disappearance of Michelle duBois, aka *Mitchi* (Fall 2012) Published by Aperture Ideas

- Volume 3: The Unveiling of Michelle duBois, aka *Cricket* (Spring 2012) Published by Aperture Ideas

- Volume 2: The Unraveling of Michelle duBois, aka *Alice Johnson* (Fall 2011) Published by Aperture Ideas

- Volume 1: The Reconsidered Archive of Michelle duBois, aka *Kathy* (Spring 2011) Published by Aperture Ideas

- Out the Window (LAX) with essays by Norman Klein, Pico Iyer, & Julian Meyers (2007)

- NTNTNT (2004)

- L.A. Now: Volume One, Published by Art Center College of Design, August 2002

ALL IMAGES COPYRIGHT ZOE CROSHER 2025

CONTACT: Z@ZOECROSHER.COM

Site by The Future.